DEVCOM

PPAN: How to Heal a Sick Nation

by Armi Jay Paragas

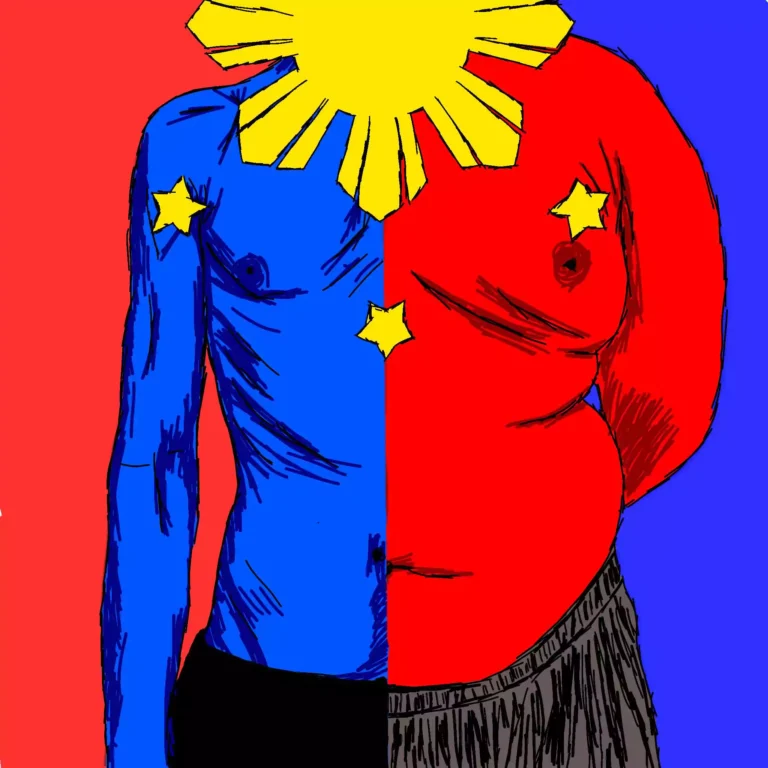

ILLUSTRATED BY: Jaime Bernabe Alonzo II

Filipino lifestyle and good health never seem to belong in the same sentence.

This is evident in all life stages of the average Filipino. Think about it. A college student’s diet is usually made of highly-processed frozen food, canned goods void of nutrients, and salty but ready-to-cook noodle soups. Some lifestyles even normalize skipping breakfast, just for the extra time either in sleep or in commute.

Meanwhile, minimum wage workers seep in their metaphorical Kool Aids: energy drinks that are advertised to keep them stronger or energized and awake – whichever the work requires. On the flipside of the same coin, teenagers indulge on their carbonated drinks in their lunchtimes. Toddlers are also notorious for consuming unhealthy foods such as candies and chips while wasting away sedentarily at their phones and tablets.

The overall consequence of these lifestyles shows whether in its raw ugliness or in the data.

That is what the National Nutrition Council (NNC) is saying through its Philippine Plan of Action for Nutrition (PPAN), an attempt to publicize the nutrition situation of the country, implement a course of action for six years, from 2023, and achieve favorable results by the year 2028.

For the 50th Nutrition Month Celebration this July, the theme, “Sa PPAN, Sama-Sama sa Nutrisyong Sapat Para sa Lahat,” is evidently centered around the plan being one of the major keys in accomplishing adequate nutrition for everyone.

However, PPAN, even the NNC, admits that there were struggles in publicizing the data and planning it offers to leaders from the barangay-level and up, as well as to families, the crucial beneficiaries of the program. Hence, this year’s celebration focuses on the dissemination of PPAN, the journey towards a healthy nation with its current situation, advantages, hindrances, outcomes, and future implementations.

Symptoms of a Sick Nation

Philippines’ current health situation revolves on what the NNC calls the “triple burden of malnutrition,” which consists of undernutrition, overnutrition, and micronutrient deficiency.

Undernutrition manifests in “stunting” or the lack of height, and “wasting” or the lack of weight; both of which mainly affects school children (five to nine years old) and below. According to the paper, the trends appear to go down but in a much slower pace than other countries.

Stunting affects one out of five children (or 21.6 percent) under the age of two and out of four children (or 26.6 percent) aging three to five years old. The statistic looks even more dire for poor and poorest households as 29.3 and 42.2 percent of children in the same age range, respectively, experience stunting.

Meanwhile, wasting is most prevalent in the two-to-five age group with one out of five children considered as underweight.

One of the presented causes of the phenomenon is the inadequate nutrition of pregnant and lactating women (PLW). A study by the Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI) shows that nine out of ten PLWs fail to meet the recommended energy, protein, Vitamin A, B, and C, iron, and calcium intake. While the underlying reason for the lack of nutrition of the PLWs is that they simply need more nutrients compared to normal adults, the data still poses an alarming situation in health of both mothers and children.

Overnutrition, on the other hand, comes in the form of overweightness and obesity. Whilst children fall victim to undernutrition, more adults seem to suffer in overnutrition.

FNRI reports that almost two out of five adults are either overweight or obese. The numbers nearly doubled from 17 percent in 1993 to 38.6 percent in 2019. It is a well-known fact that overweightness contributes to a variety of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and high blood pressure. Obesity is also linked to mental health problems as it can be weaponized for discrimination whether in the family, within peers, or in public.

In the Cordilleran landscape, the condition is more visible. According to a 2019 study by Imelda Degay from Benguet State University’s College of Home Economics and Technology (CHET), it is observed that 56.7% of workers in the regional line agencies are either overweight or obese. The study categorized their nature of work based on movement and almost half of the participants were documented mostly sitting in their work hours. Region-wide, Cordillera ranks second, just next to National Capital Region (NCR), among 17 regions in the prevalence of overweight and obesity.

As pointed out, sedentary lifestyle seems to be one of the contributors of this metric as adults consists of workers that lack physical activity. Most labor, especially office works, usually involve sitting for long hours, putting the health of adults at risk and causing them to go overweight. In addition, adults tend to cook affordable and convenient but less nutritious meals to maximize time for sleep or commute. Adults are also less inclined to do physical activities such as recreational sports which younger age groups usually have. Lastly, the proliferation of vices like alcohol and smoking in adult lives amplified the effects even more.

Finally, micronutrient deficiency is evidently present in all ages. For instance, PLWs already suffer from lack of nutrient intake as mentioned earlier, while nine of ten adolescents also have calcium, iron, and Vitamin C inadequacies.

With these findings, PPAN pointed out that the nutrition problem does not only exist in childhood but is also present in other stages of life, from pregnancy to late adulthood. Since the issue takes in different ranges, PPAN made sure to incorporate their solutions inclusively with what it calls the “life stage approach.”

Universally Inclusive but Specific

What is new to this 2023-2028 version of the PPAN is the recognition that proper nutrition should occur in all stages of life, not only in childhood that previous programs usually emphasize. However, it was made clear that different stages have different major problems that require different types of intervention.

For example, nutrition implementation on PLWs differ from that of adolescents and adults because PLWs require specific needs and even infrastructures. A good example is the addition of lactating stations in non-health public places such as malls, airports, and terminals. Some laws such as the Kalusugan at Nutrisyon ng Mag-Nanay Act (RA 11148) that enunciates the importance of the first 1000 days of a baby from birth in its growth and development and the 100-Day Expanded Maternity Leave Law of 2019 (RA 11210) that gives more time for the mother’s health to recover, as well as for the baby, cater exclusively for the PLWs.

Going up in the life stages, preschool children are the beneficiaries of the National Dietary Supplementation Program (NDSP) wherein children aged two-to-five enjoy nutritious food packs through their respective daycare and child development centers and local government units (LGUs).

Education on nutrition is also needed; hence, the National Nutrition Promotion Program for Behavior Change is organized. The program facilitates the celebration of Nutrition Month and National Breastfeeding Awareness Month in July and August, respectively, among all sectors of the government, most especially the education sector. After all, school children and adolescents play a huge role in overall information dissemination on the nutrition situation of the nation.

Unfortunately, not all plans came to a fruitful outcome. For instance, the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion Law of 2017 (TRAIN Law) aimed to discourage Filipinos from buying sweetened and carbonated beverages by increasing the tax for the said products. Despite this, the overweight and obesity numbers remain troubling and the prevalence of diabetes is still prominent, even in younger age groups.

Problems like this, however, are not easily solvable by tweaking a specific aspect. Instead, it requires not only multisectoral approach, but also holistic, striking the roots of social norms.

Social Problem, Health Problem

Immediate causes for malnutrition were already brought out in the first section of the article, but the underlying social causes also needs to be addressed as such are the root cause of the presented problems.

One evident social problem is the restricted accessibility of nutrient-rich food, whether economically or logistically. It was mentioned that Filipinos tend to gravitate towards less healthy food because of their accessibility, convenience, and affordability. In some cases, transported goods such as vegetables can reach inflated prices or be even outright unavailable in urban areas, whether due to poor supply planning or natural disasters. A typical Filipino family would happily take on what their money can afford and what is readily available.

In relation to the previous point, aggressive advertisements on these unhealthy foods appear on television, radio, and social media alike, further amplifying its reach. In a World Health Organization (WHO) analysis, almost all food advertised in the social media were deemed unhealthy to children. Moreover, ads on breastfeeding substitutes were particularly prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic, disrupting the traditional practices of breastfeeding.

Unsurprisingly, the private sector is something the public has little control of; hence, the government is expected to be the public’s companion in health and nutrition. The lack of political will and the alienation of the LGUs were the main problems pointed out by the PPAN. Barangay-, municipality-, and city-level leaders play a pivotal role in the distribution of the goods and services brought by the plan. However, many seem to lack political will to do so, going as far as not being aware of the PPAN itself. This is obvious when zooming in into the organizational charts of health units that are void of nutritionist-dieticians. Other LGUs rely on part-time experts brought in by volunteer groups and non-government organizations (NGOs). Even units with nutrition experts still suffer from high turnover rates, causing local programs to freeze or be compromised.

Finally, these plans on national nutrition seem to have a common symptom: lack of human resources. PPAN claims that the human resources are being overwhelmed by the number of plans and programs currently ongoing. The problem appears to be rooted on the uncertainty and unsustainability of the projects currently being implemented.

There are many other different social causes that plague the current health situation in the forms of natural calamities and unwillingness to integrate nutrition in the education curriculum. But whatever the causes may be, the consequence appears the same: an unhealthy nation struggles economically.

Estimates from the Cost of Inaction Analysis by United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) imply that undernutrition costs the Filipino economy almost Php 250 billion in 2017. Looking at the situation, one should see how the nutrition situation relies on the different sectors of the nation such as agriculture, economy, education, social welfare, and interior and local government. Hence, the PPAN repeatedly stated that the plan for a healthy nation requires a multisectoral approach and the willingness and cooperation of these sectors to drive malnutrition away.

UNICEF Philippines Representative Oyunsaikhan Dendevnorov emphasized what the nutrition aspect of the nation means, “Every child has the right to proper nutrition. When children are well-nourished, they can better learn, play, and engage in their communities, while also being more resilient in the face of illness and crises. Good nutrition is a fundamental driver of development and is essential for nation-building.”

With proper monitoring and evaluation of data and the capability to adapt to it, it can be made sure that the Philippines is trending to a healthier, more sustainable nation. Malnutrition is a common enemy, why are we even hesitating to defeat it?