CULTURE

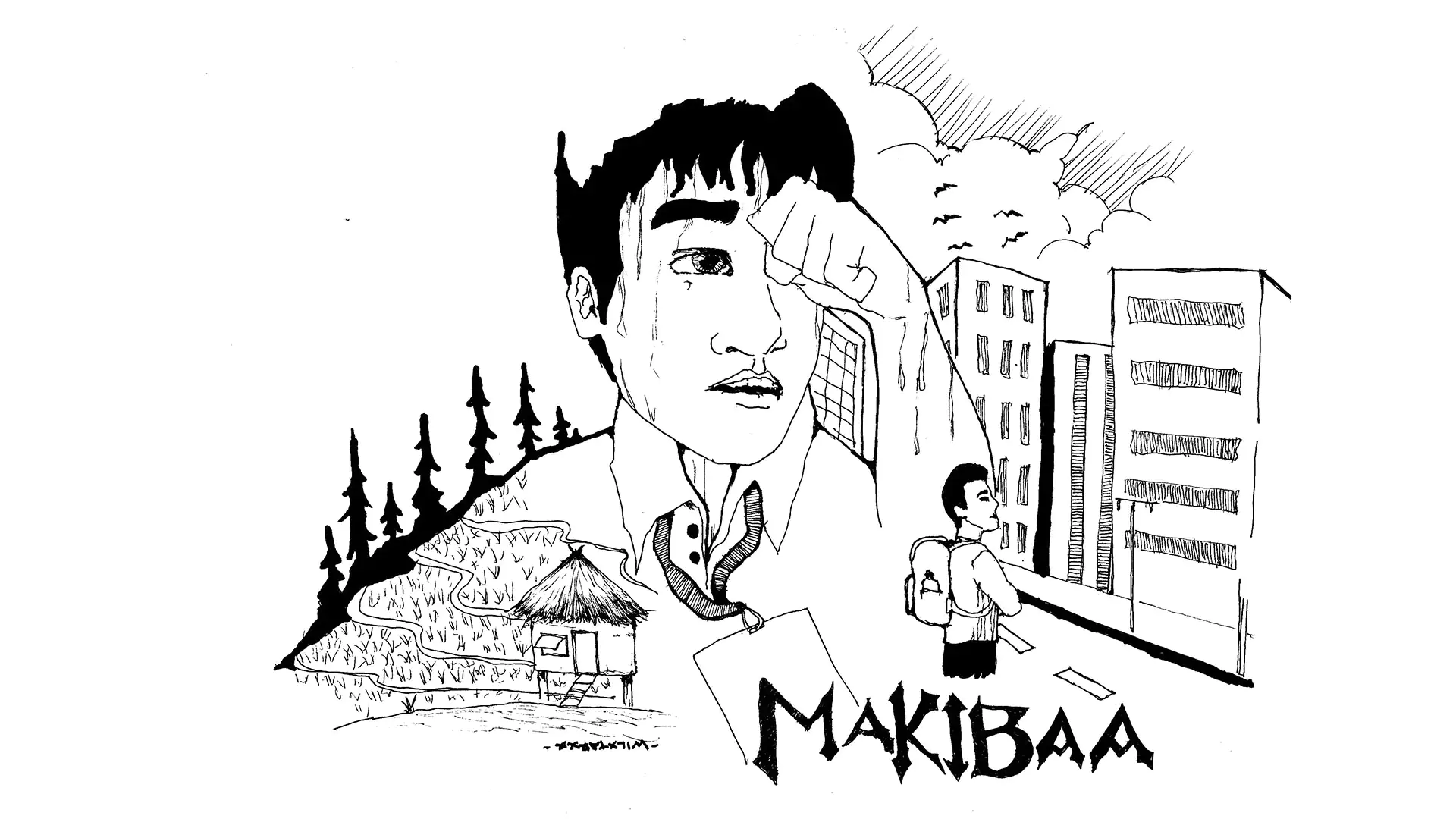

Makibaa: Stories of Intergenerational Baas

by Karen Gayang, The Mountain Collegian alumni / originally published as a development communication article in The Mountain Collegian Magazine Vol. 48, Issue 1 (August 2019 – December 2019)

“Memorable and enriching encounters with foster families, classmates, teachers, and neighbors”, are the advantages of the baa or the makibaa practice.

Imagine someone 12-13 years old leaving the comfort and warmth of their homes in pursuit of a better future. Instead of living with their families, the youth chose to move out of their homes to pursue their education.

This was revealed in a study by Leonardo Samonte, Center of Culture and the Arts director at Benguet State University (BSU), titled “Makibaa: The living out experiences among the iMiligan of Upper Bauko, Mountain Province.” Young children, termed as Baas are being permitted to venture in the lowlands leaving their families behind to pursue their dreams on their own. This practice is becoming a trend where young people of Miligan depart from their families and live with non-relatives in the lowlands for better opportunities. The practice was long started before 1970’s however the number of Baas increased from the 1970’s to 1990’s until today.

Baa refers to a foster child who lives with foster families in exchange for help mostly in household chores such as scrubbing the floor, cleaning, washing of clothes, and preparing food among others. This developed the Makibaa practice where the child leaves their biological parents and live with foster families. Through them, adoptive families are relieved of minor works around the house which propelled their neighbors to request and invite Baas to live with them as well. Thus, causing the increase of Baas moving in the lowlands. Consequently, people who refer a Baa should have been acquainted to or have personal knowledge on the attitude and financial capabilities of the prospective foster parents.

Due to financial constraints in augmenting school expenses such as transportation, board, and lodging, parents are forced to send their children to the lowlands in exchange for such. The residents’ source of income depends only on farming explaining why they do not have enough money to finance their children’s school expenses.

The research noted that the development of values and skills and the referrals of former Baa through their narrations of good experiences and transformations being acknowledged by the iMiligans attracted other young ones to do the same. Moreover, with the desire that their children may be successful, parent’s motivation added to the youths’ drive and allowed them to follow the footsteps of successful baas they had heard of.

On the other hand, government agencies’ lack of support to provide the basic needs for the academe such as classrooms, school facilities, and items for teachers and the inaccessibility of schools in remote areas prompted iMiligan children to go and continue their studies in the lowlands. With this, the increasing number of drop-outs or flocking of students in the lowlands resulted to incomplete grade levels in the schools.

As cited in the study, the Municipality of Bauko belonged to a fourth-class municipality. This was further elaborated by LAWPHiL.com stating that these municipalities have an average annual income ranging from three million pesos but less than five million pesos. Moreover, the lowlands where the Baa go (Pangasinan, Ilocos Sur, La Union, and Nueva Ecija) are classified as first-class municipalities where their average annual income is fifteen million pesos. This accordingly is the reason why the Baa chooses to move to the lowlands that have improved infrastructures and accessible schools over their place of origin.

Other than dwindling school performances experiences of sexual harassment, a high rate of teenage pregnancy, and early marriage alarmed parents to send their children to the lowlands to become a Baa instead.

Nonetheless, the relationship between a Baa and a foster family is intimate at times that they regard each other as a family. In this case, even when the Baa is no longer under the care of the foster family their connection remains intact.

“My first foster family was so good to me. Even when I was with another foster family in Manila during my tertiary education and when I worked abroad, our communication line was still there,” expressed Maria David in the study.

However, some Baa unfortunately had to go through undesirable treatments with their foster families. Since they were just Baa, other family members treated them as house helpers and were subjected to verbal or physical abuse. As cited, one discriminating treatment is the deprivation of basic necessities such as food. Yet, whenever the Baa is deprived of this need, they accordingly become resourceful by setting aside food without permission and by climbing trees for its fruits.

Separate shelter provided for the Baa also seemed discriminatory in the sense that the Baa does not belong, but some Baa regard this as a better setup for privacy. Additionally, the Baa experiences irregular sleep patterns because they have to wake up early in the morning to do household chores. Even so, they considered this experience as a good foundation and an advantage when they finally entered tertiary education. Lack of financial allowance also forced the Baa to resort to other methods by choosing to walk to school rather than ride a tricycle and instead use the transportation allowance to buy snacks.

On the other hand, being miles away from family develops the feeling of loneliness and homesickness among the other iMiligan. Some Baa were able to cope but others who could not decided to quit and go back home.

In school, while other classmates treat them well despite their cultural upbringing, economic status, and the knowledge that they are a Baa, bullying and discrimination were still noted. During these times, teachers become Baa defenders and neighbors serve as their motivators and inspire them to stay and work hard even more.

The Baa compensates their foster families when they are treated fairly while they endure the negative attitude and treatment from them by being humble, meek, and apologizing. They continually strive to show that they are not different from others until others learn to accept them. And, in order to let out the feeling of homesickness the Baa employs coping mechanisms such as crying, sending letters to their families, and spending time with their fellow Baa. Making themselves busy also helps them relieve the feeling of yearning for their loved ones.

With all these experiences, the Baa learns to adapt strategies and responses in every treatment from the people around them.

As such, with this practice of Makibaa, the researcher recommended that Government agencies together with Local Government Units (LGU) should prioritize and give attention to infrastructure projects, educational equipment, roads and transportation, and dormitories or boarding houses among others. Foster families who will be acting as the Baa’s second parents must be given commendation. However, the researcher stressed that they need to undergo orientation and guidance in handling foster children.

Indeed, being a Baa is packed with memories and enriched by the people around them, is a life-changing experience for the young people of Miligan. Young as they are, taking the courage and accepting the risk in pursuit of better education and opportunities are manifestations of unwavering determination towards their hope of success.

The intergenerational baas not only embody the determination and perseverance of the youth in pursuit of their dreams as manifested in Makibaa but encapsulate the characteristics of a Cordilleran being able to conquer the challenges of poverty and difficult access to education towards self-empowerment and success.