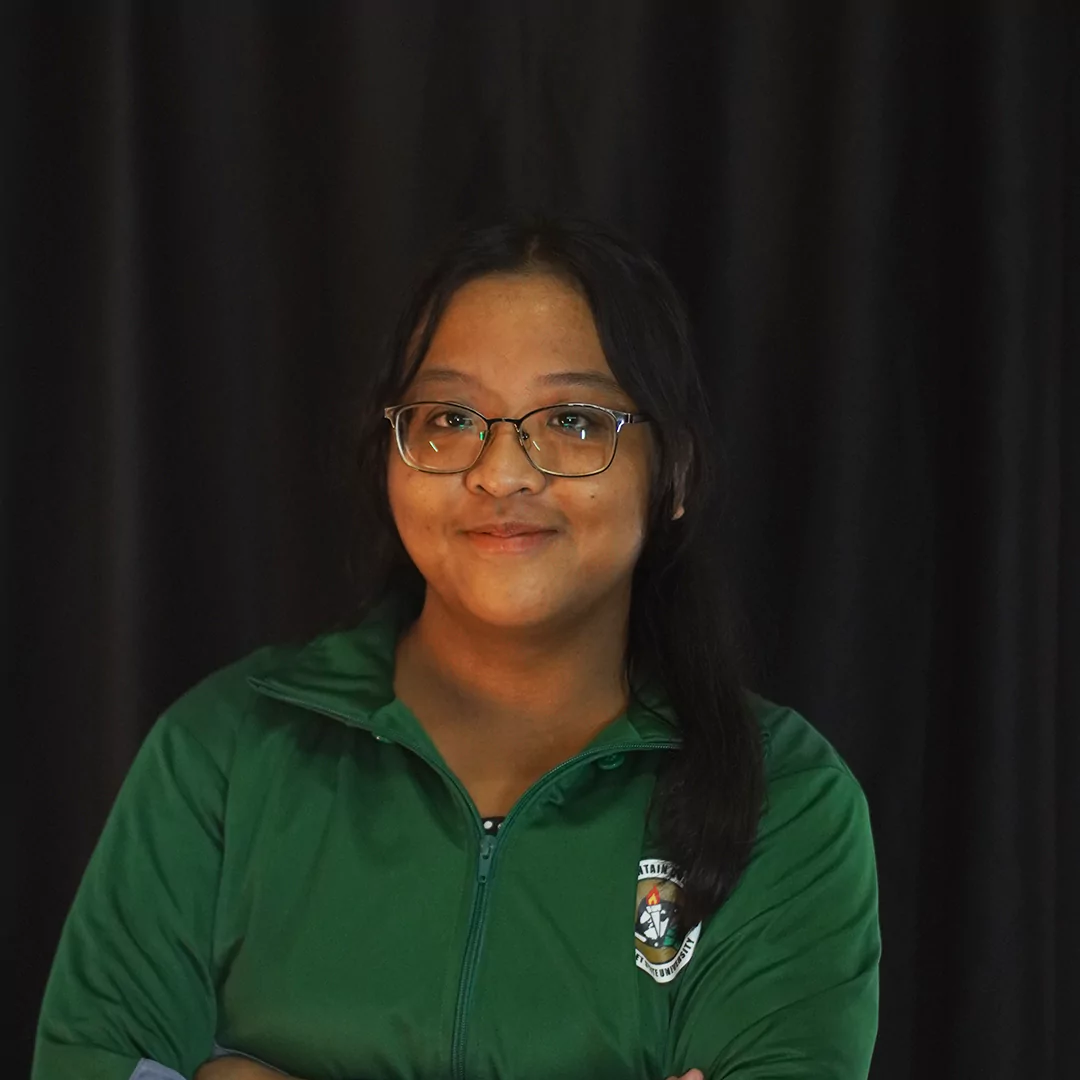

the official student publication of Benguet State University.

The Mountain Collegian (MC) is the official student publication of Benguet State University (BSU). Since its establishment in 1963, MC has been more than just an ordinary publication by empowering the students and giving them a platform to raise their voices, printed and archived in the pages of history.

The Mountain Collegian Print Department

The Mountain Collegian Broadcasting Department

The Mountain Collegian Multimedia Department

Investigative Beyond payrolls: An inkless contract of uncertainty by Liezhel joy ramos|Category: Investigative Journalism |Originally published as an Entry to

CULTURE Of Igorot Native Delicacies by Suzette Joy Palantog Nowadays, modern food tend to dominate or influence the taste buds

Opinion AI naku: Dehumanizing Journalism by Liezhel Joy Ramos | Column Article Surprise suprise! Misinformation, Disinformation, and Oppresion of Press

CULTURE Hinagpis ng Nakaraan: Himig na Dumadaloy sa Bawat Tono ng Kasalukuyan BY Aubrey MendegorinIsa na ata ang dulang Macli-ing

investigative Workers Plight in an Inkless Transaction by:Jaime A. Bernabe II (published November 17,2024)Working for a job can be tiring

RESEARCH News is News: The State of Media and Campus Newspaper Practices among students in Benguet State University by Rosella

For enquiries, comments and suggestions, you may visit us or contact us through the following channels:

Our Office Address:

SC 101, Student Center Building, Office of Student Services, Benguet State University, La Trinidad, Benguet 2601

Email Address: [email protected]

Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/the.mt.collegian1963

Alternatively, you may also fill out and submit the form below: